Can reading a map make you a better musician?

In the last few weeks, I have been deep in the weeds. With maps. It started with discovering the Atlas Catalá, (Catalan Atlas), a mappamundi from 1375 thought to be created by the Majorcan cartographic school, a collection of predominantly Jewish cartographers and mapmakers working in Mallorca before Spain’s expulsion of the Jews (1492). It highlights known locales and their religious/political allegiances. The text is oriented towards the edge of the page since readers would have walked around a table to read

The mappamundi piqued my enduring interest in maps. How about this one, this map, a copy of which has been hanging in my parent’s house as long as I can remember:

A French version of the pilgrimage routes to Santiago de Compostela. The cities are not hierarchical with regard to size, but with regard to their religious and geographic significance: who visited where, what is on the way to where. In fact, the map lists some “fan favorite” routes on the right hand side. It has all the trappings: crests of the Spanish Monarch and the House of Bourbon, the cross of St. James, and a nice call to arms (“Dios, Ayuda, y Santiago”). It even has decorative boats taking on the pilgrimage route by sea, just in case those dotted lines over the ocean weren’t clear. In typical French fashion, most of Spain has been replaced with images of St. James as a pilgrim, adorned with his go-to scallop shells.

While the above is certainly a modern invention, it’s based upon the tropes of 17th century map making. I love that this map is a one-stop shop, rolling cultural history, politics, and travel planning into one convenient package. More importantly, this could be a map one reads on the way somewhere, much like my beloved Michelin maps, which I love to unfurl imagine the terrific places one could go.

Happy place: map store

Speaking of routes, what about the Romans, who by many accounts did not use geographically signifying maps?

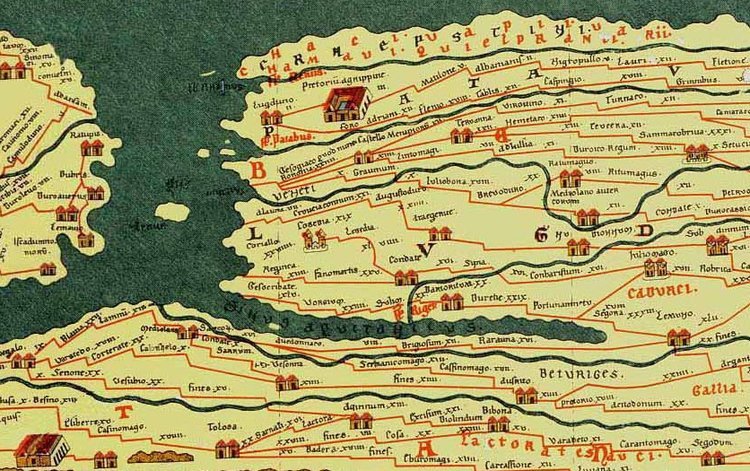

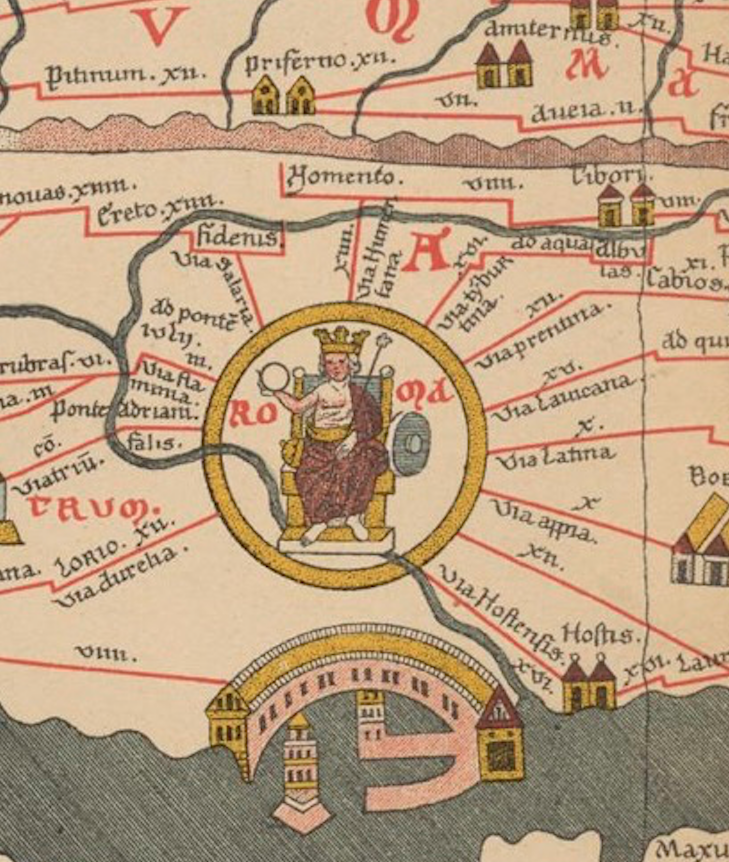

Instead, they navigated with itineraries (itineraria) which directed travelers from milestone to milestone along the Roman cursus publicus (road network). These are scenes from the Tabula Peutingeriana (Roman itinerarium), a 13th-century of an original from around 12BCE and later engraved in marble in the Roman Campus Agrippae.

Check out the full size Tabula here 🤯

These are schematic maps, deemphasizing geographic features in favor of connections. Here milestones on the cursus are depicted in parallel lines (north is left). Since most travelers would not have had a map, the most salient information would be “what is the next city I’ll pass” and “how far away is it.”

What do maps have to do with contemporary music, the supposed subject of this newsletter?

Reading a map is an interpretation:

All maps have a bias, from the choice of projection, to the selection of a scale (unless you are Borges), to the curatorial decision of what to include (my beloved Michelin maps sure do include a lot of roads), these biases range from passive, to active, like this amazing rendering of the Washington DC Metro by Andrew Bossi:

Generally speaking maps say more about the people making them than about the places that are being mapped. Who is the map for? A king isolated in their castle, or a travel writer exploring the world? Who is it not for? What is left out, kept in?

More importantly, (most) maps need somebody to read and interpret their biases. That reader brings their own contemporaneous ideas to the reading. Sounds an awful lot like a point famed musicologist Richard Taruskin makes in Text and Act, where he argues that performance practice of 17th and 18th century works says more about the society performing them than the “original intent” of the composer. In fact, arguing that “original intent” is an important parameter is a uniquely modern idea. I think all of us who have seen a Shakespeare play set in a post apocalyptic future world or a Verdi opera set in a 1950s office can make sense of this argument.

2. Maps and prescribe and describe

My mind keeps catching on the juxtaposition between prescription vs description so elegantly expressed in maps, particularly the Roman Tabula above. That maps is prescriptive—it tells the reader what to do rather than describing the world.

In his 1958 article “Prescriptive and Descriptive Music-Writing,” musicologist/folk musician/Bob Dylan listener Charles Seeger argues that musical notation can be either prescriptive or descriptive. In prescriptive notation, the emphasis is on structures (typically structures of pitch and meter). The notation does “not tell us much as much about how music sounds as how to make it sounds.” Descriptive notation endeavors to display the work “as it is,” through graphics of sound waves or other means.

I have been thinking this week about musical scores, and how most musical notation is prescriptive or symbolic. Sometimes, a score might include so many prescriptions that the implication becomes that what is essentially prescriptive is in fact a description of the music, requiring no other input from a performer and no other historical or intuitive insight. Our scores are most effectively is abetted by oral performance practice traditions: performers who have worked closely with performers, composers sharing (passively or actively) their notions of a range of acceptable interpretations.

So what are we as interpreters to do? We have a very clear distinction between text and the performance of that text. (Whether that should be the case is a subject for another newsletter) Stated a more proactive way, art needs people to grapple with it, and need communities to make sense of the people making sense of the texts.

3. Maps are mental representations

With the arrival of a new semester, I, like my professor brethren, have a renewed vigor around what we teach and how. In particular, I’m more interested than ever and how we learn, particularly how we learn music.

Central to our learning in music is the notion of a mental representation. Popularized by Anders Ericsson in his book Peak, a mental representation is “a mental structure that corresponds to an object, an idea, a collection of information, or anything else, concrete or abstract, that the brain is thinking about.” More to the point, they are worldviews. These conceptions of the world can broadly be construed as mental representations. Although motor learning experts might rolled her eyes at my definition, I believe a mental representation is a multi sensory sense or perspective developed through exposure and practice about why something is the way it is, and more importantly, what is wrong when something is wrong.

Now, is a map a mental representation? Your answer might immediately be no. Most maps are created so that people don’t have to remember the location of information, or a culturally significant location. But, they are. A map represents an idealized (to someone) version of a place. A lot is left out, and those omissions are in many cases very purposeful distinctions. Is this not a sense of how things should be, a worldview? A super heuristic?

This year, I’m interested in how teaching can be about helping people bring color, nuance, and perspective to their mental representations. If one’s students have a strong sense of how things should be, they can effectively teach themselves. But, it is not enough to have a sense of what is right, how a piece of music should sound. One must have the critical perspective to indicate and understand why your perspective is but one of many. In fact, aren’t our most epiphanic experiences the ones through which a new piece of information conflicts or rubs against our current conception of the world?

As performers and teachers of music, our goal is to facilitate not only a rich sense of the way things should be, but a critical lens on why you might believe what you believe about what you believe. So, we tend to learn by comparing what we don’t know something we do know. If you know maps, get ready to learn about music.

Now, is a map a mental representation? Your answer might immediately be no. Most maps are created so that people don’t have to remember the location of information, or a culturally significant location. But, they are. A map represents an idealized (to someone) version of a place. A lot is left out, and those omissions are in many cases very purposeful distinctions. Is this not a sense of how things should be, a worldview? A super heuristic?

This year, I’m interested in how teaching can be about helping people bring color, nuance, and perspective to their mental representations. If my students have a strong sense of how things should be, they can effectively teach themselves.

But, it is not enough to have a sense of what is right, how a piece of music should sound. We must have the critical perspective to indicate and understand why our perspective is but one of many. In fact, aren’t our most epiphanic experiences the ones through which a new piece of information conflicts or rubs against our current conception of the world? As performers and teachers of music, our goal is to facilitate not only a rich sense of the way things should be, but a critical lens on we believe what you believe about what you believe. we tend to learn by comparing what we don’t know to something we do know. If you know maps, get ready to learn about music.

Ok, back to *Transit Maps of the World*.

Mike