Welcome!

I am a percussionist, music-lover, chamber musician, teacher, curator, writer, and life-long learner.

I’ve moved most frequent updates to my two newsletters:

Older news below:

NEWS

Practicing Flow Chart

I’ve been thinking a lot about practicing. As a university professor, I spend a lot of time berating my students for not practicing enough, but that’s only part of the story. In reality, I should berate them for not practicing more effectively…or…not berate them at all…?

I was not an effective practicer while in school, prone to binges on single techniques, long forays into a single action, and hopeless attempts to memorize music too quickly. In recent years, my practice routine has become more focused, more individualistic, and, paradoxically, more creative.

Learning to learn is the single most essential outcome of studying music at a university. As such, developing effective, flexible, and individualistic practice habits is the quintessential task of the student musician, the most essential ingredient in the pivot from talent to skill that demarcates the professional from the amateur.

In an effort to not have my students repeat my mistakes, clarify my thoughts on practicing and give my students a framework for effective individualization of complex musical tasks, I made a flow chart, documenting what I felt could be important touch points in each practice session:

Pre-practicing (score study, familiarization)

Warmup/technical development

Ingestion

Refining

Incubation

My idea was that an effective practice session can and should cover each of these poles, though the weight will vary according to individual needs. In each step, I encourage my students to incorporate the rigor of Deliberate Practice and the experimentation of Design Thinking. These steps also roughly hew to what we know about how our brains most efficiently learn new skills. I also thought of examples of other types of practice sessions, from aggressive drilling of musical material to a mock audition.

I’d love to hear what others think. For me, practicing is a moving target, learning from others’ best practices can only enhance all of our work. At the same time, I’d love to hear from current students, since it can be easy to mistake causation for correlation when reflecting on one’s individual experiences.

Recording in the Practice Room

This semester at ASU, I’m presenting on a number of skills that successful musicians should have.

We’ve been talking as an institution about how recording oneself has become an essential skill for 21st century musicians. At the same time, I’ve been thinking about how to teach good practice and time-management habits. These concepts meet in on the issue of recording oneself in the practice room, so I am sharing some thoughts below about how I use recording in my practice.

Why Record Yourself?

As I’ve discussed in a previous post, learning is a combination of experience and reflection. Recording jumpstarts this process by allowing the experience to be observed from a number of perspectives without worrying about time, which allows for a more nuanced, critical reflection. More experience + more reflection = more learning!

Similarly, recording provides instantaneous, unbiased feedback about your playing. One of the central tenants of both Deliberate Practice and Design Thinking is that learning requires feedback. With recording, feedback is immediate, and unbound to our biases about our playing. When we learn, we struggle when presented with what David Epstein calls “wicked” learning environments: situations in which feedback is not immediate and in which previous experiences do not imply a future strategy. Because of its immediacy and objectivity , recording oneself in effect turns a ”wicked” learning environment into a ”kind” learning environment.

How? Recording aids in the development of mental representation around our playing, and is like having a teacher in the room with you. In Peak, Anders Ericsson explains that a mental representation is “a mental structure that corresponds to an object, an idea, a collection of information, or anything else, concrete or abstract, that the brain is thinking about.” Thus, “the main thing that sets experts apart from the rest of us is that their years of practice have changed the neural circuitry in their brains to produce highly specialized mental representations, which in turn make possible the incredible memory, pattern recognition, problem solving, and other sorts of advanced abilities needed to excel in their particular specialties.” When we record ourselves during practice, we supercharge that developmental process.

Recording also meshes nicely with the problem solving strategies espoused within Design Thinking, which prioritizes brainstorming many ideas and quickly testing them. Recording is perfect for these tandem processes of ideation and prototyping.

How I use recordings differently than some of my colleagues

My philosophy around recording myself differs from a “pure” application of Deliberate Practice. While Deliberate Practice has as its stated goal the refinement of a narrow band of outcomes (“this is the way”), buttressed by a guru and a clearly-defined learning modality, I prefer to use the tools of Deliberate Practice to achieve the skills of generalization, flexibility, and creativity. Deliberate Practice is both a technique and a philosophy. I prefer the technical elements, but want to avoid the implication that our end goal is perfection of a single performance practice.

My musical goal is to be able to play everything in myriad different manners, and so I use my recording to help develop maximal flexibility. Why is flexibility better than honing one way? In Range, David Epstein demonstrates that those with extreme domain specific knowledge and narrow bands of pattern recognition can’t adapt to new situations. And since you’re going to be working with lots of people who will ask you to change things ASAP to get $$, flexibility seems a valuable and pertinent skill.

What You Need

Good Quality Audio In and Out

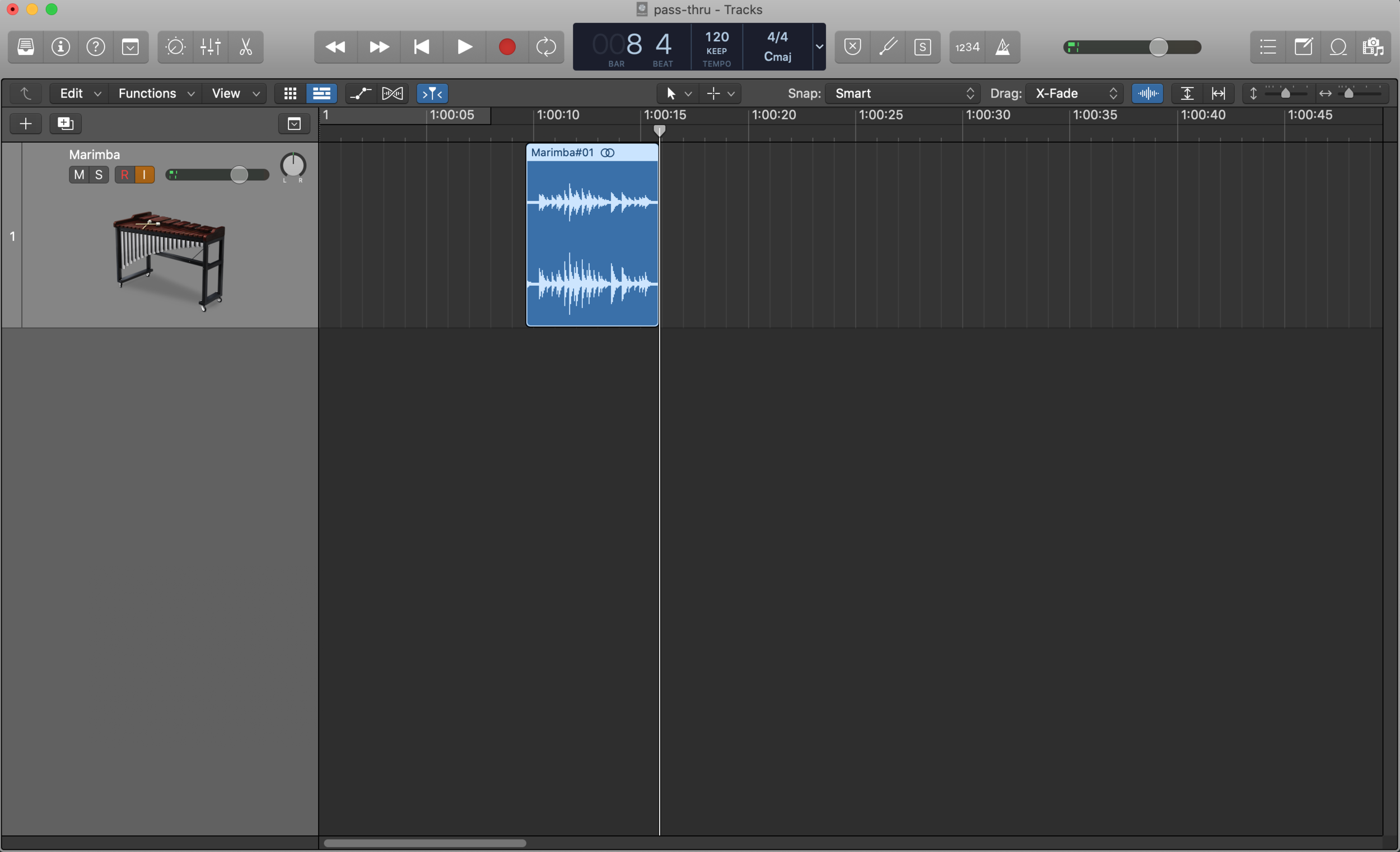

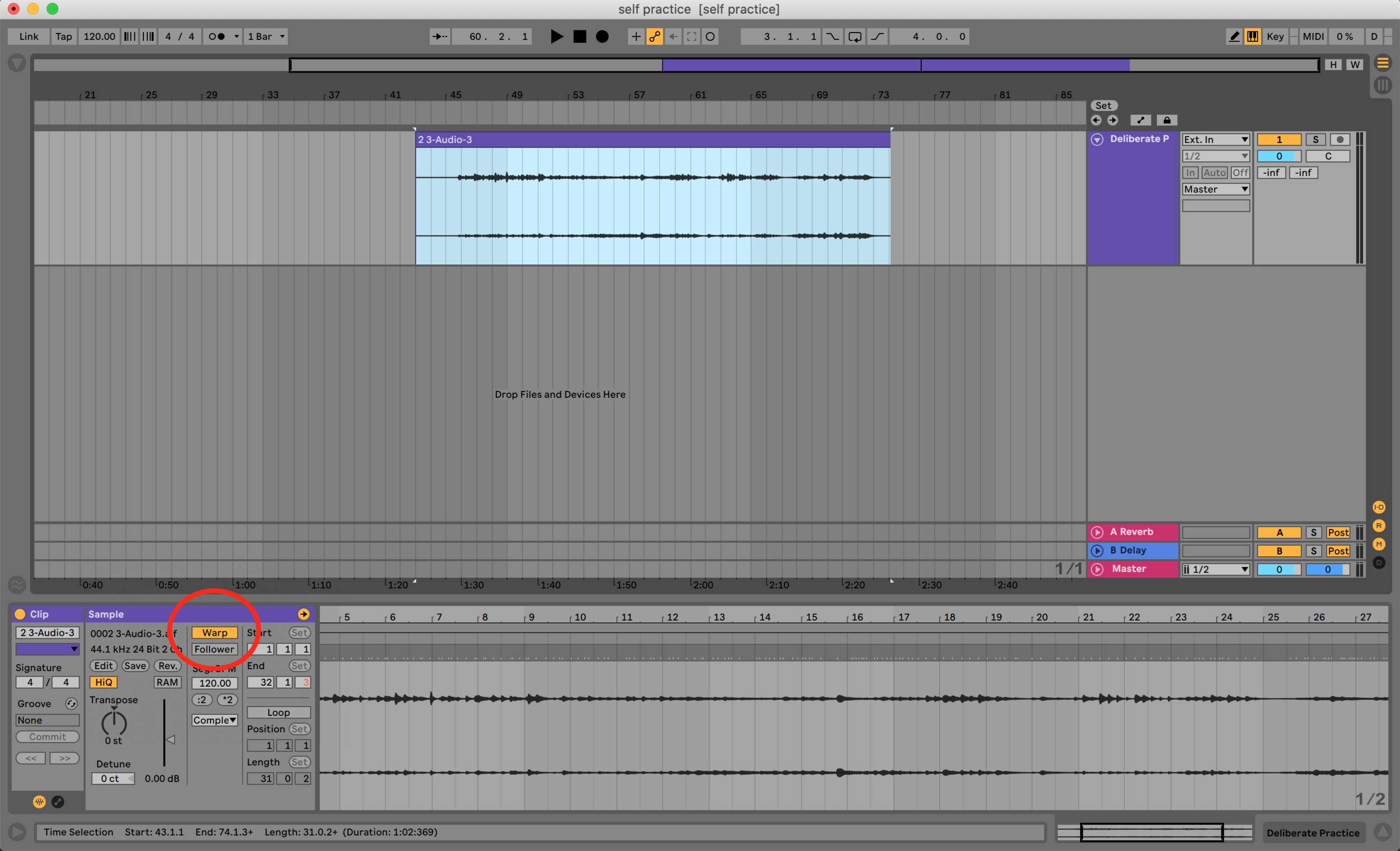

My setup is stereo mics with audio interface and either Logic or Live. I prefer recording into software rather than to a standalone recorder because I like being able to quickly edit audio, loop passages, and compare against previous recordings while using visual and software inspection of waveforms as a quick check of my precision and consistency. On the road, I typically use a Zoom H4 or H6 for quick and dirty recordings. USB microphones are terrific these days, and the plug and play element is very helpful. Make sure you allow plenty of cable length to get a good sound from your sofa—I mean marimba. Personal preference is salient in DAW choice, so try a few out and see what works for you. I use a combination of Live and Logic: Logic because I’m comfortable with the interface for recording and editing, and Live for the ease of changing the tempo of my recordings.

If the goal of our practice is to refine and develop our sound concept, we need good output as well as input. Either good headphones or good monitor speakers can help you make quality decisions about your sound.

Peabody’s list of recommended equipment is a good jumping off point if you’re just getting started.

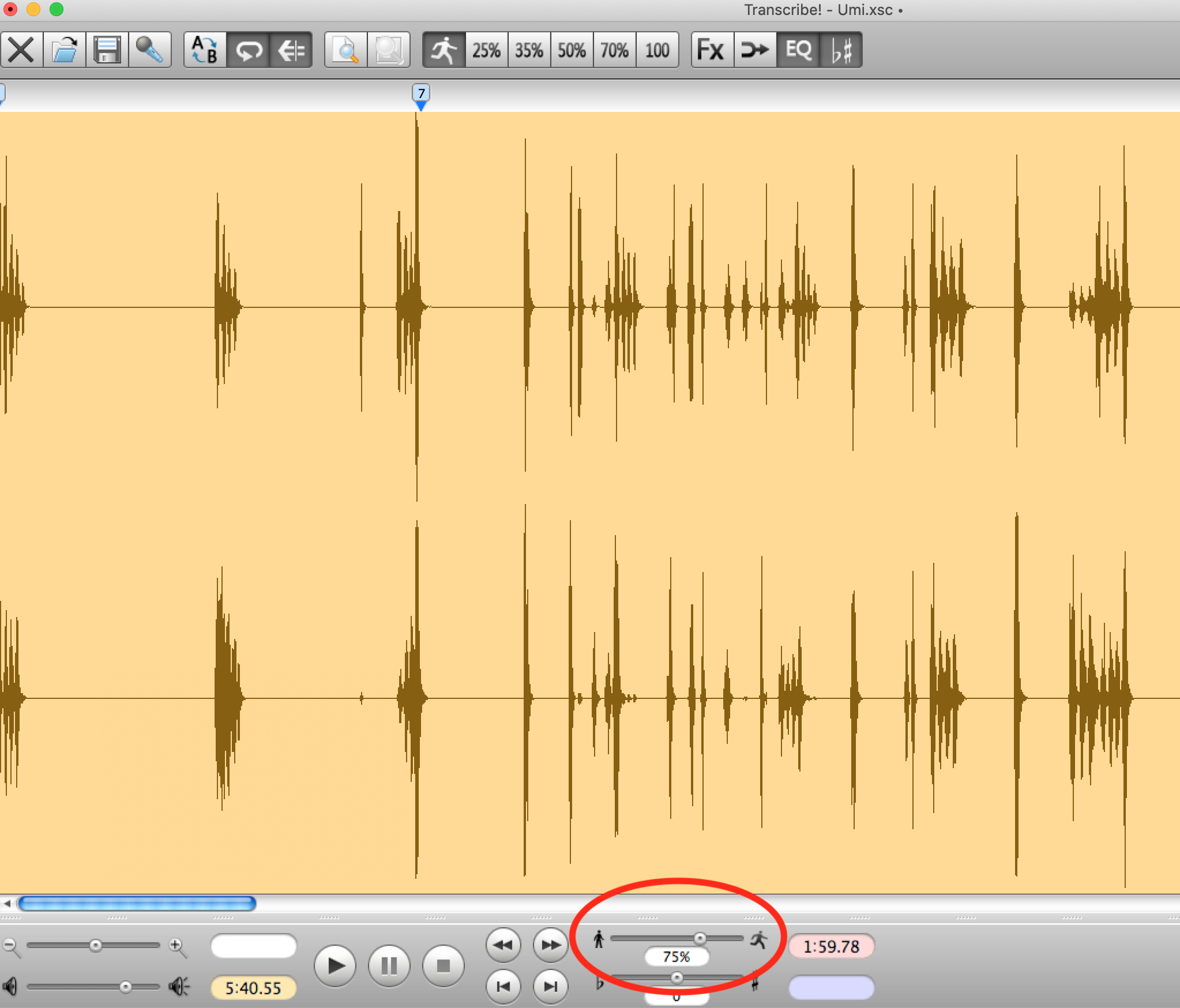

The Ability to Slow the Recording Down

I like to slow down my recordings to more accurately assess issues. Although most DAWs can change tempo without impacting pitch, Ableton Live’s warping feature is perfect for real-time adjustments. Transcribe! works wonders as well, although importing sound files into the program can be just slow enough to discourage me from using it.

Notebook/Practice Journal

I use a notebook (well, a OneNote notebook, sorry Todd Meehan), to keep track of my notes, and to make assignments for myself. I tag assignments and then periodically review and summarize my goals so that I can always enter the practice room knowing what I need to accomplish.

Why no Video?

I typically record audio only in my practice sessions. Why? Video can lead to unnecessary bias. We have a tendency to listen with our eyes, saying that a passage sounds a certain way because it looks a certain way. It opens the door for dogma, and it’s a slippery slope towards the kind of narrow-banded thinking which cripples specialists. That kind of subjectivity is the opposite of what we’re trying to achieve when we record ourselves.

Finally, working with video is incrementally more challenging than working with audio. Video files are slightly more challenging to edit, and the larger file sizes are moderately more annoying to manage. ”Moderately more” is enough to discourage me from recording (I read Nudge, didn’t you?), so I keep things to audio unless I’m working with larger chunks.

Recording Situations

Lessons

Goals: documentation, reflection, synthesis, goal-setting

In a lesson, we pay close attention to our teacher’s words and actions. We throw ourselves into trying things in new, uncomfortable ways. Great teachers are masters at pacing, so after a terrific lesson we might not remember everything that happened. That’s where recording comes in. Students who record lessons improve exponentially.

How-To

After asking your teacher if you might record your lesson, record the lesson. Then, get to work. My philosophy on lesson recordings aligns closely with Mike Truesdell’s three stages of learning: Analysis, Synthesis, Application.

Analysis

Listen back to the recording, making a written summary. This summary should be detailed enough to give you plenty of homework, align with your practicing themes, and also be capable of serving as reference matter in the future.

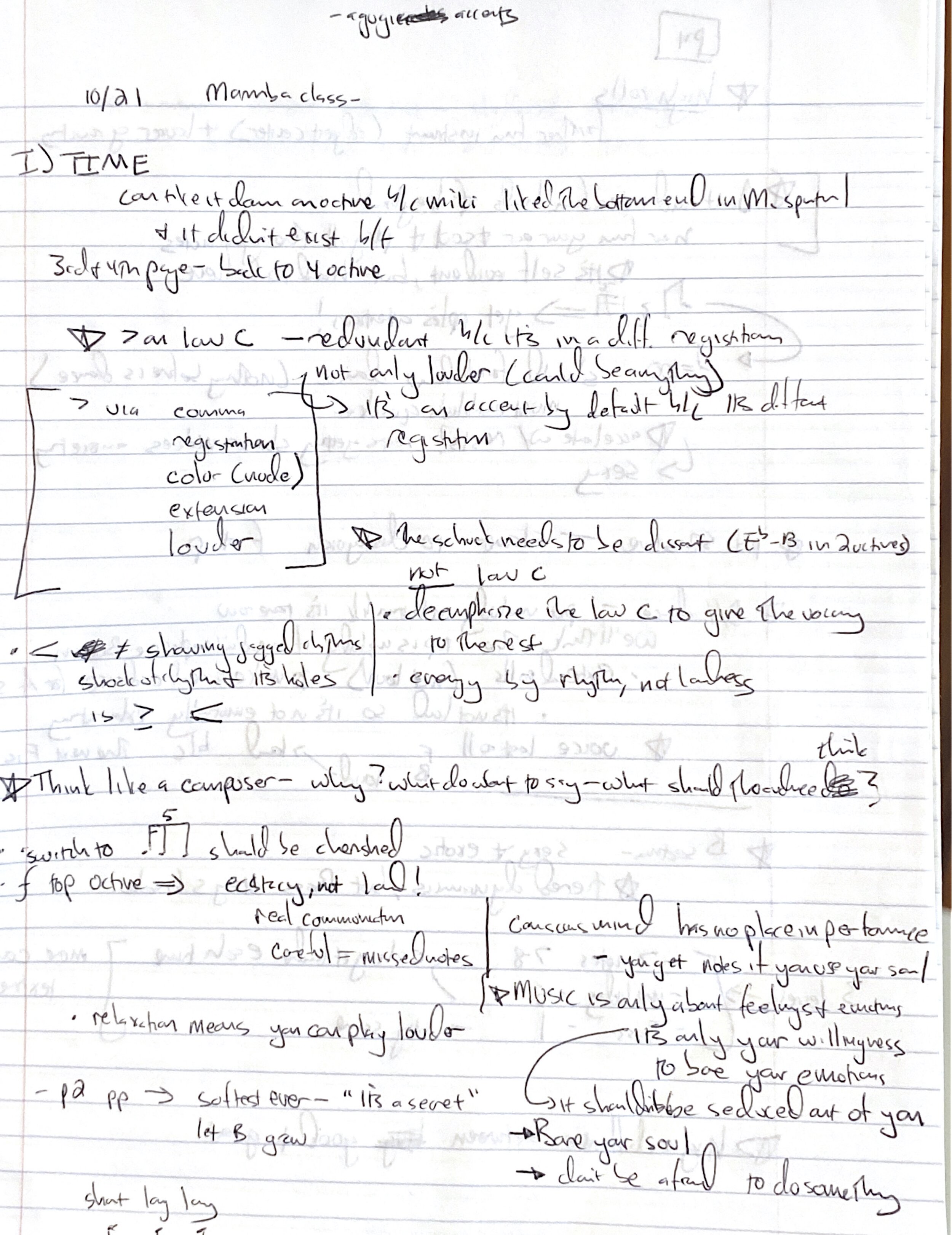

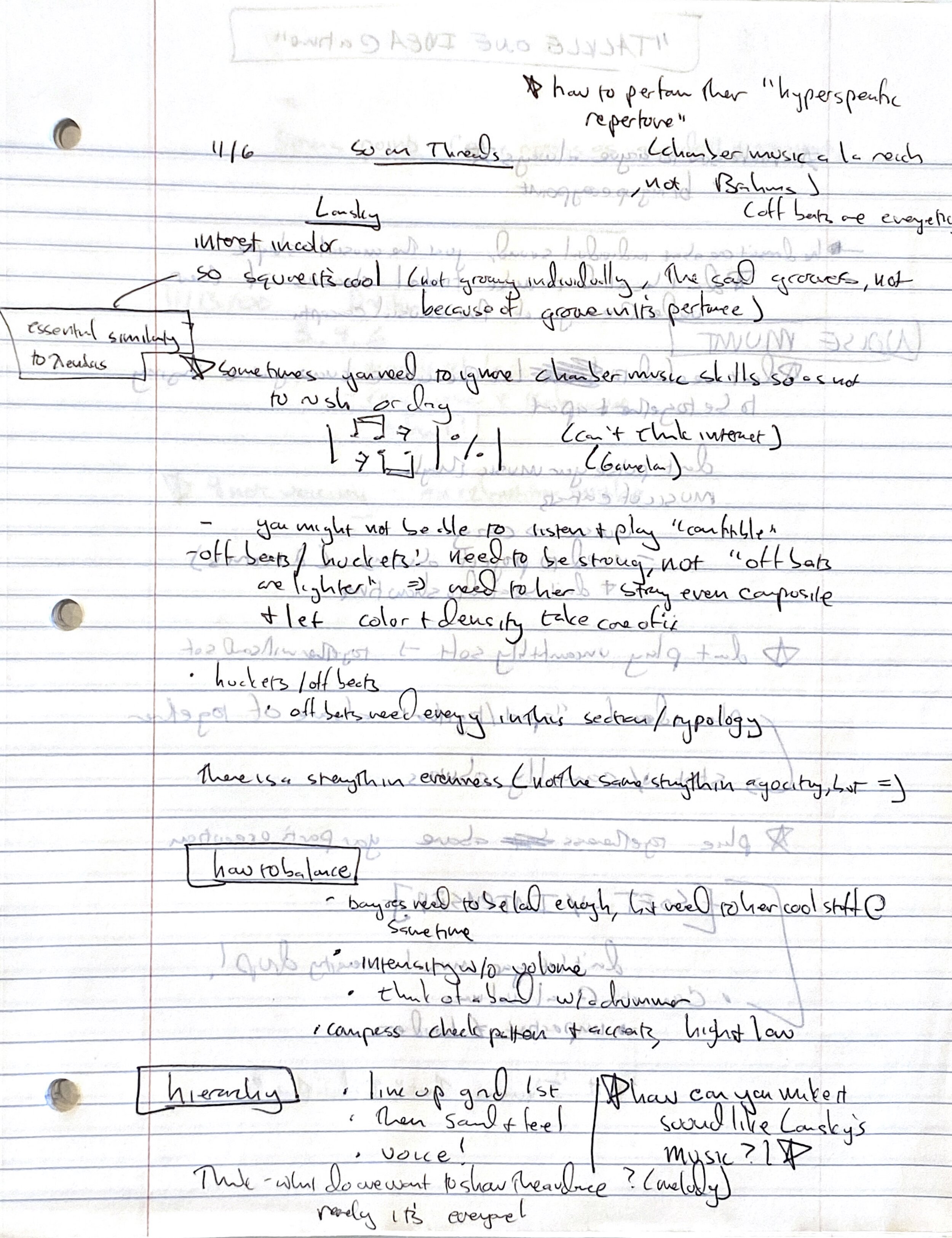

Here’s a summary from a lesson I took as a freshman at Peabody on Minoru Miki’s Time for Marimba, and on a coaching of Paul Lansky’s Threads. In both cases, In both cases, I tried to both summarize what happened in the lesson and provide some higher level organization of the more free-flowing events. Almost 20 years later, I have almost no problem remembering this content, although I still can’t read my own handwriting.

Then:

Assess your ability to change in the moment: were you doing what the teacher asked? Many times we think we’re making a concrete change, but our emotional biases blind us. Hearing the recording may explain why your teacher consistently asks for the same changes over and over and over.

Synthesis

Make a list of your key takeaways from the encounter. These ideas should focus your future practicing. Similarly, make sure to mark your music in accordance with the content of the lesson. Stickings, character markings, anything that you didn’t have time to mark in the lesson should make their way to your music. I recommend this step even if you think you’ll remember everything. On the one hand, multi-modal learning is essential for durable knowledge. On the other hand, studies show that our memory fades much more quickly than our perception of our memory. In other words, write it down!

Application

Create goals around your key takeaways, trying to make note of everything your teacher said. Great students don’t need assignments from teachers. One lesson should be enough content for weeks of work. My key takeaways from Jason Haaheim’s visit to KU “Great students bring problems to diagnose, not mysteries to solve.“ Your lesson recording should help you to try everything you can to make own your learning.

Practice Sessions: Ingestion

Goals: Get closer to your mental representation while prototyping methods of developing mental representation

How-To:

Pick a spot to work on, starting with smaller spans. Record yourself. Listen three to four times and make smart notes. I listen first for musicianship, and other big picture ideas, then for timing, then for intonation or tone quality, and finally for accuracy. Broadly speaking, I proceed along 2 paths from this point.

Option A

If you have a clear idea of what this passage should sound like, check your recording against your mental representation. Give yourself specific, detailed notes. “It sounds bad” is both poor grammar and poor analysis. “Eb in measure 5 is sharp,” or “consistently missing jumps between a 2nd and an octave in measure 2” is better, but still not great grammatically.

Then, make a smart, quick, repair, tackling one issue, using every practice technique you can think of.

Option B

What if you don’t know what’s wrong? You hit all the right notes, but something sounds off. If you don’t have one for this passage, but know something is not quite right, proceed with Option B, which is influenced by Design Thinking:

Brainstorm potential issues. Prototype a variety of changes, interpretations, or other variants. Try these quickly, and assess the effects. Perhaps inventing some exercises around the musical material can help focus your ears and hands? Then, proceed, circling back to option A.

Practice Sessions: Incubation

Goals: Refine your interpretation, combat stage fright by practicing performing.

How-To:

Choose a medium-sized chunk of music. Record yourself, and listen back, making specific comments on trouble issues. Categorize these problems: are these randomized occurrences or consistent? Small things (missed notes, bad transition), or systemic—a lack of dynamic contrast or tendency to compress fast passages? Make notes on the limits of your dynamics, tempi, character. Are they too narrow, too wide? Is your timing perfect?

Make a change, using the techniques outlined above. Tackle consistent issues first, then think about the larger issues.

I like to record in the medium scale because it helps me tackle performance anxiety. When we practice, our goal is to think critically about our own playing, diagnosing issues and planning our next steps. When we practice, that immediate feedback is a recipe for disaster. We can hone our performative skills by putting ourselves into “performance” mode, knowing we have our recording to help my critical thinking later. Over time, one can quickly enter this reflexive performance mode more readily. On this point, using a medium sized chunk is essential. Too often we practice our performance skills by making full runs of pieces. This is akin to jumping from a warmup to a marathon, with no smaller races in between. Not a great idea.

Performance Review

Goals:

Compare your memory of a performance to how it actually sounded.

Learn how to account for acoustics: timing, timbre, instrument choice

Refine the effectiveness of your portrayal

How-To:

Listen back to a concert performance, comparing your memories of the event to the recording. Does it sound the way you imagined? If not, what is different? Orchestral players will frequently use their colleagues or recordings to help hone their sound in different acoustics, calibrating their sense of their sound up close with the reality from hundreds of feet away. In chamber music, I find listening to a performance at a later date can help me calibrate my interpretations: did that moment land the way I wanted it to, or was my inflection too small for the space?

Some other recording situations worth mentioning:

Recording as Object

Goals:

Practice making a recording

Hone the skills of being a studio musician

Develop recording and editing skills

In recording studios, small scale inflections are less important, and larger consistency is more important. We can’t hear tiny details that really speak in live performance, but we do hear errors in timing and consistency, especially with percussion instruments.

Recording sessions are tiring, and have unique energy flows: long periods of low activity pierced by bursts of high-concentration. Why not become accustomed to this pacing by making a recording of a piece you know fairly well?

Similarly, making a demo recording can help you develop the skills of tracking and editing a piece. If you’ve been using recording in your practice, you’ve built up some technique within your DAW. By building upon the technological foundation you’ve developed in recording your practice sessions over a long period of time, you can put your new skills to work!

What to Do With the Recordings?

When Jason Haaheim visited KU, he shared his computer desktop with the percussion studio for a Powerpoint presentation. As his curser careened across his desktop to click “start slide show” (BTW, there’s a keyboard shortcut for this!), we messy, disorganized onlookers glimpsed the Jedi Archives: a perfectly organized database of excerpt recordings. I was in awe. Wouldn’t it be great to have everything I had ever played in one place?

This was ALMOST the moment!

My conclusion is: not really.

Although I do have a record (recorded or written) of almost every lesson I have ever taken, I treat my practice room recordings like post-it’s: a temporary memory aid whose value diminishes as its number increases. A desk full of Post-it’s is worse than no Post-it’s at all.

Why?

Similarly, I believe that I want to create what David Epstein calls ”wicked” learning environments (see last week’s post) when I practice, testing myself to remember what I was doing and how at precisely the moment that recall is challenging. Thus, my recordings often sound terrible.

The larger reason that my practice recordings are not valuable to me as documents, though, has to do with my larger goal in practicing. And they are not important to me as documents, since I believe in preparing to play something in infinite different ways, not honing in on one interpretation

I’d love to hear how you use recording in your practice routine. In the meantime, happy analyzing!

Mike's Summer Book Club (Extra-Long Edition)

I’ve always read from diverse topics, ranging from analytical tracts about supply chains during the Revolutionary war to Elmore Leonard to Murakami to works on the display of statistics. In the past five or six years, though, I’ve read much more from non-musical domains, and have found that the cross pollination induces some fantastic critical, lateral, and creative thinking (see below).

Over my forced sabbatical, I’ve read heavily on our nation’s contentious and immoral past. But, a stream of other works has emerged within my reading, connected by the desire to connect psychology to biology. Here are some thoughts on them.

Bibliography:

Burnett, Bill, and Dave Evans. Designing your Life: How to Build a Well-Lived, Joyful Life. New York: Knopf, 2016.

Epstein, David. Range: How Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World. New York: Riverhead Books, 2019.

Haidt, Jonathan. The Righteous Mind: Why Good People are Divided by Politics and Religion. New York : Pantheon Books, 2012

Newport, Cal. Deep Work: Rules for Focused Success in a Distracted World. London : Piatkus, 2016.

Thaler, Richard H., and Cass R. Sunstein. Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness. New York: Penguin, 2009

Richard H. Thaler and Cass R. Sunstein: Nudge: Improving Decisions about Health, Wealth, and Happiness.

Choice is good. More choice is great. Freedom to choose is terrific. But is it? Richard H. Thaler Cass R. Sunstein make the case that humans are predictably irrational. We know the correct course of action, but frequently ignore the facts in favor short-term interests, cognitive biases, and other irrationalities. Thus, public and private institutions can preserve our ability to choose while simultaneously affecting behavior through careful choice architecture.

Econ vs. Human

Thaler and Sunstein lay out a conception of humanity as alternating between a rational, self-interested ideal and a biased, short-sighted, easily swayed groupie. For the former, Thaler and Sunstein use John Stewart Mill’s notion of Homo Economicus: a conception of mankind as rational, self-interested, and utilitarian. Homo Economicus is a contrast to what Thaler and Sunstein dub Humans: those of us afflicted with cognitive biases, irrationalities, and other localized mental hindrances. (As I’ll discuss later, this duality roughly parallels Jonathan Haidt’s conception of mankind as a fusion of individualists and group opportunists).

While Homo Economicus, what Thaler and Sunstein call Econs, can asses data without emotion, make careful judgements based on available information, and act to promote their self interest, Humans are trapped within their biases. Mental accounting, framing, anchoring, mapping, availability bias, over confidence, and relatability (among others) make Humans \ irrational, set by our evolution to act via heuristics in the short term.

Whereas Econs utilize reflective systems—where information is assessed without prior biases—humans use automatic systems, an outgrowth of our fight our flight impulses. One thinks fast, the other slow (that’s a book for another blog post).

Thaler and Sunstein argue that while well-meaning system designers strive to provide maximum choice for their members (ever signed up for a health care plan as a university employee?), maximum choice without transparent and concrete information about each selection does not always benefit those of us with cognitive biases. I know I, for one, curl into a tiny ball when trying to pick out a completely customized drum set. Choice Architects should instead put system members in a position where they can accurately evaluate their options and make an informed decision in spite of our biases. In short, we require nudges; small system cues which can highlight better options even when we are impaired by bias and fear.

Thaler and Sunstein apply nudges to situations ranging from health care plans (don’t make the default option no coverage!) to climate change, to cell phone warranties (don’t get them) to urinals (make a target and few people will miss), and to fundraising (apply a “twice as much tomorrow” approach). While the book tends towards behavioral economics, the authors’ emphasis on the inner conflict between Humans and Econs is a useful lens with which to critique our own decision making both on the individual and systemic level, and to examine the way in which we can acknowledge our biases and embrace out inner Econ.

(Some) Takeaways:

Be aware of your biases!

As a musician, my biases can be a strength. But off-stage these preconceptions can be problematic. Thaler and Sunstein outline a few which seemed pertinent:

Framing

We react strongly to how a problem is presented to us. Aren’t we more likely to buy insurance against floods than heart attacks?

Anchoring:

How much would you be willing to pay for something if you heard its average price was $400,000, vs $100,000? By mis-anchoring our decisions, humans can misjudge and misalign priorities.

Nudges and “Anchor Problems”

In Burnett and Evans’ Designing your Life: How to Build a Well-Lived, Joyful Life ”anchor” problems are issues where one parameter appears to be both essential and immovable. “I need a garage, or else everything stinks!” Burnett and Evans discuss many solutions to reframe and diffuse anchor problems. Perhaps these issues can be positives as Human reactions, rather than Econ reactions. Maybe we all need a little more Econ when faced with intractable life issues: that garage workspace could be a spare bedroom, etc?

Representativeness

When we judge an unknown option, we tend to base our judgment on assumptions which tend to be highly inaccurate. It’s easy to see this in our judgements of people (“nerd!”), but Nudge made me think of Representativeness with regards to housing, insurance, musical gear, and all sorts of other instances where lack of data causes us to behave…strangely…

Status Quo Bias

Humans seem remarkably content to keep things as they are, even if it contributes to a general worsening of one’s situation. Defaults are powerful, and if a choice architect can set a positive default option (enrolling in a 401k, or being an organ donor or helping a friend), they should do so. Maybe setting the default credit option to 1 when enrolling in collegiate orchestra would help our credit count?

Happiness

If one’s sense of self worth is based on the opinions of others, one faces a difficult road full of nauseating snaps between the beliefs and priorities of others. What other people have, do, and say has an outsized impact on Humans, and only with a well-defined sense of self can we maintain our well-being

Jonathan Haidt: The Righteous Mind: Why Good People are Divided by Politics and Religion.

In The Righteous Mind, Jonathan Haidt explores the seemingly impermeable cultural, political, and social differences which frequently stymie us, arguing that our divisions could be better framed as a differing set of key moral principles. Could it be that those who espouse a radically conservative agenda are not (as liberals believe) crazy and impossible to comprehend, but rather prioritizing other frameworks of morality? Haidt builds upon his work in India and his extensive study of American political parties to articulate a set of moral foundations, principles which guide our actions.

While the essential conceit of The Righteous Mind is to explore the moral foundations theory that Haidt claims can explain why we don’t understand one another politically and culturally, I found the more pertinent question of the book: why do humans group together? What’s the value of joining a group? Why would an Econ display “groupiness” when at our our core we are evolved to behave in our self interest?

Like Thaler and Sunstein, Haidt argues that humans do not consistently function as Homo Economicus, our purely rational selves. Neither are we consistently reliably Homo heuristicus, Homo reciprocans, Homo sociologicus, or Homo politicus. Instead, Haidt adopt’s Durkheim’s model of homo duplex, a being which moves between two forms of social consciousness: a lower level framed by self interest and individual attainment, and a higher level where one pursues collective group goals.

Haidt’s conclusion is that human nature is ”90 percent chimp and 10 percent bee.” Humanity’s deepest biological core is individualistic, more concerned with winning than virtue (as in Glaucon and his story of the ring of Gyges). But, we have a more recent neurological overlay dedicated to “groupish” behavior. Bees’ competitive impulse is between groups, not between individuals, and Haidt’s research shows that modern humanity is descended from earlier humans “whose groupish minds helped them cohere, cooperate, and outcompete other groups.” Humanity is selective in how we take part in groups, and our participation in group activity can be an indication of both our selfishness and our desire (also born of evolutionary biology) to have our group advance.

Haidt’s foray into evolutionary history is fascinating and went a long way to convincing me that our human morality has a very clear biological origin. At the same time, Haidt’s work further elucidates the biological foundations of both Humans and Econs

But, Haidt’s more pertinent innovation is to connect these notions of Econ and Human to evolutionary biology and neurology, to argue that the link between our individualism and group impulse is morality. Moreover, Haidt posits a framework for understanding how and why humans can be selfish AND group based: moral foundations.

The Moral Foundations

The main focus of The Righteous Mind are Haidt’s six moral foundations. These frameworks help govern our desire to join groups, to engage in selfish or selfless behavior, and to understand one another. Haidt argues that these foundations are biological, forged from thousands of years of evolutionary “nudges:”

Care/harm: Mammalian attachment + ability to feel the pain of others

Fairness/cheating: reciprocal altruism, justice, rights, autonomy

Loyalty/betrayal: tribalism with shifting coalitions was essential to our development as a species, and seems to be essential for virtues of patriotism, and self-sacrifice for a greater group good.

Authority/subversion: Hierarchical social interactions —> leadership, deference to authority, and respect for traditions

Sanctity/degradation: Our biological aversion to disgust and contamination becomes notions of living an elevated, less carnal, more noble lifestyle.

Liberty/oppression: resentment of the restriction of personal liberty

Why are some people happy in political, social, and economic frameworks that others would consider exploitative, repressive, or unfair? Why do we have so much trouble understanding those with differing political viewpoints? Haidt argues that we all operate under some ratio of the moral foundations, and that these differences result from priorities placed on different moral foundations.

Take Aways: What does this have to do with drums?

Politics

Not surprisingly given his previous writings, Haidt’s work tilts towards the political. How can liberals understand conservatives? What are the weaknesses in each side’s political theory, and how might they be explained not as immutable signs of mental instability but by adherence to a different set of moral codes? Haidt argues that much of the gulf between American political parties can be explained by a misalignment between the way liberals and conservatives apply moral foundations to their work. In Haidt’s view, liberals rely predominantly on the Care/Harm foundation, supplemented by the Fairness/Cheating and Liberty/Oppression foundation. Conservatives, though, tend to use all six moral foundations, leading to some blind spots in the way liberals perceive conservative morality.

In addition to the politics, I found great application in Hadit’s synthesis of Mill, Durkheim, and others in the fields of education, community building, and shared experience.

The Hive:

Why do humans take part in group behavior if it doesn’t immediately benefit us individually? Haidt’s tour of soldiers, college football, church communities, cults, and other groups show us that morality “binds and blinds.” These moral communities are not really centered on their features—college football is not about football—but rather on the feeling of belonging and togetherness that flipping “the Hive Switch” can generate. A great insight, but I found particular joy in Haidt’s digression to discuss scenarios when one can encounter the Hive rush while alone: in fantastic natural surroundings.

Neo-liberalism in Universities

The expansion of liberal (small L) values in universities seem to be a great idea. Universities have gone to great lengths to ensure that students from more diverse backgrounds are admitted, that student voices are heard, and that in turn must create a more powerful university system. Haidt’s moral foundations seem to imply that this liberalistic impulse—the desire to highlight care/harm above all else—erodes Authority and Sanctity, both essential to developing strong minds and productive societies. As someone who wonders why my students don’t listen me or why people don’t seem to trust experts anymore, Haidt’s foundations show the danger of overweighting one moral foundation at the expense of another. Maybe more music students could activate their Authority matrix and listen to their teachers with more alacrity? Or maybe my percussion studio can be more of a hive?

Musical Communities

As musicians, we deal frequently in building community around the work we make, honing connections between composers and performers, performers and audiences, and audiences and communities. Thinking about the moral foundations as modes of interactions and engagement can help us form groups in which empower their members while understanding and celebrating our differences. Finding that hive feeling is essential to music making, and acknowledging the role morality plays in binding us can help performers and audiences find that community, even while we operate at a distance Maybe we could even nudge group members towards supporting a cause we believe in?

Likewise, the moral foundations can help us as teachers in understanding the priorities of our students. I used to think about core values as an organizing trope for my work with percussionists, but Haidt’s moral foundations can help explain the types of musical and personal goals we set as teachers and students.

As a teacher, I’ve always thought that I could tailor my message to fit a students’ learning style, but I haven’t considered how my students organize their moral foundations could help me make better connections with them.

I know I draw upon the sanctity/degradation and authority/hierarchy often in my teaching: “you have to play this piece this way because that’s how the composer told me to play it and because I said so.” At the same time, a strict curriculum might benefit those who value authority, loyalty and fairness, but alienate those who value liberty and personal creativity in their learning. I’m thinking that a re-evaluation of my moral foundations as a teacher and community leader can help us take on issues of social change more readily.

David Epstein: Range: How Generalists Triumph in a Specialized World

Our world values specialization: we pick a sport at a young age, most college degrees push us towards a narrow specialization, job titles are increasingly specialized (and lengthy). But is specialization as essential to professional success and personal self-actualization as we are led to believe?

David Epstein draws upon research the biology of learning and case studies of success in a variety of fields to push back against what he calls the Cult of the Head Start, the idea that focusing on a skill or career at an early age is essential to success.

Epstein argues that those with the most success in certain fields tend to be generalists, with a broad array of experience from a variety of domains. While specialists—broadly construed as those with high domain-specific knowledge but little expertise outside their field—have incredible skill, their narrow band of knowledge can create problems when faced with unfamiliar learning environments.

Wicked and Kind Learning Environments

Epstein argues for the value of specialization by articulating two types of learning environments. In a “kind” learning environment, feedback is immediate. One knows whether a choice was correct or a move perfectly executed. There exists a pre-ordained idea that the student strives toward, and other adherents’ previous forays can inform the acolyte’s journey forward. For example, one can study historical chess matches, learn the pertinent patterns of the game, and receive almost instantaneous feedback on a match well played. Or, one can study the violin, where a teacher can indicate in a lesson what was successful, what failed, and offer guidance down a clear path of technical improvement. The way is clear, the material vetted, and the didactics are based on the application of patterns and algorithms which have worked in the past.

By contrast, a “wicked” learning environment contains none of these helpful cues. A decision is made, and no feedback is given. The problem appears similar to another previous issue, but shares no structural similarities. What worked in the past doesn’t seem to work now. Epstein argues that in these wicked learning environments—seen everywhere from investment management to scientific research to contemporary music—the lack of both immediate feedback and a clear-cut procedure creates pressure for solutions based on experiments rather than experience.

Success in wicked learning environments requires bias free analysis, a broad skill set, a wide and diverse toolkit of problem-solving skills. To Epstein, the so-called “domain specific knowledge” specialists have can be dangerous, because it seems to limit our ability to adapt to new challenges and wicked learning environments.

Specialization

For those of us in academia, specialization is a powerful tool, both in advancing original research, and in creating metrics to measure that research. Silos are meaningful to us, because stye both protect knowledge from short-term fluctuations, but also allow us to build upon previous research without reinventing processes or paradigms.

While Epstein doesn’t negate domain specific knowledge’s power, he argues that taken alone, specialists’ reliance on pattern recognition and previous experiences can make adapting to new problems a severe problem. Specialists have a tendency to over-rely on familiar solutions and previous experiences. They assume kind learning environments, drawing conclusions without accumulating data, and they look for solutions from within their domain at the expense of simpler, more elegant solutions from outside their field. Epstein is right when he argues that “knowledge is a double-edged sword: it allows you to do certain things, blinds you from other things.”

In his research, Epstein demonstrates time and time again how groups of specialists fail in wicked learning environments, and how teams of people with different backgrounds and more generalized skill sets seem to solve problems with more flexibility and elan. Why? Generalists are more willing to try “outside-in” thinking, to eschew cognitive bias in their problem solving, and to think of what might work instead of what worked in the past.

Key Conceits and Takeaways

Our Non-Musical Reading Lists

I was enthused reading Range. I always felt that my propensity to read outside of music was a weakness, a sign that I wasn’t as passionate about music as I could be. Perhaps thinking a lot outside one’s domain can bring real rewards when returning to your home field?

Nudges and Wicked Learning Environments

In Range, Epstein makes a distinction between “kind” learning environments (where feedback is immediate, and where there exists a set curriculum for developing a skill) and “wicked” learning environments: where feedback on our choices is not immediate, and where there may not exist a set curriculum, methodology, or other way of learning something. Thaler and Sunstein’s work essentially argues that we need nudges in wicked learning environments, where previous experience does not dictate future success, or where feedback on our choices is not immediate.

Durable and sticky learning is wicked, not kind

Where Range can be a powerful tool for educators is Epstein’s ability to draw a connection between wicked learning environments and what he calls “sticky” learning, knowledge that doesn’t fade quickly. (Think of how easily you can remember a phone number but how quickly you forget as soon as another digit enters the mind).

Specialization and Econs

Specialists tend to exhibit the cognitive biases Thaler and Sunstein attribute to Humans, but they tend to tout them as strengths rather than blind spots.

The Long and Winding Road

Like Haidt, Epstein goes a long way to linking our intuitions and philosophical constructs with human evolution and our biological imperatives. That said, my largest critique of Epstein’s work is the self-selection is his case studies in winding career paths.

In addition to problem solving, Epstein argues that generalists also tend to have more fulfilling careers because they have a stronger “match quality” with their work: their skills and personalities match perfectly with the challenges and needs of their job. People who have broad skills often spend a long time developing those skills, and as such have experienced a number of types of work and can choose effectively what suits them . Generalists tend to take a winding path to their career, going through what Epstein dubs a “sampling period” to discover whether a job or profession is a good fit. If not, the generalist will proceed to something else. Match quality is greatest with a successful sampling period, and a successful sampling period is precisely that: a length of time (not picking up karate at age 3 and never deviating). Wicked learning environments can flummox even Econs, so we should have a learning style capable of tackling the most wicked environments, which is formed during a lengthy and fitful sampling period.

This point is clear. The generalist is a design thinker, a prototyping experimenter who values short term ideas that can succeed or fail quickly. That said, Epstein’s cherry-picked case studies don’t completely eliminate the existence of Tigers, those who have a passion, hold to it, and change the world around their dreams.

Analogous Thinking and Outside-In Thinking

As someone whose teaching evaluations frequently tout (for positive and negative reasons) my propensity towards analogies, I appreciated Epstein’s Kepler-inspired foray into the power of analogies I problem solving. Analogies can help us break free from knee-jerk reactions while pushing us to identify structural similarities in problems, not surface similarities. Analogies help us avoid what Epstein calls “the inside view,” the specialist idea, a framework based entirely on domain-specific knowledge. If we can think of snare drumming as like cooking an egg, we can go a long way towards more durable problem solving.

Measuring Learning

Epstein argues that many of our methods of measuring learning don’t measure durable learning, and as such we draw the wrong conclusions on the quality of our teaching and the relative import of short-term success in a classroom or professional arena. We can all do well to prioritize long-term learning, despite the challenges in measuring it.

Range + Design Thinking + Econs

A number of Epstein’s case studies dovetail with the central principals of design thinking. Generalists tend to be design thinkers: they make short term prototypes, test the results, and move forward. They also tend to be more Econ than Human—they don’t let past experiences color their future analysis, they are not inhibited by cognitive biases. Whereas Epstein’s cadre tended to look for short term growth as a measure of personal fulfillment, a pure design thinking approach highlights the experimentation element. That said, a number of key points elide with the main ideas of Design Thinking, including:

Being a scientist about oneself, making short term experiments instead of not long-term plan

Working forwards from promising situations instead of backwards from a goal

Range and Deep Work

While this post is far to long to cover my deliberately-paced exploration of Cal Newport’s Deep Work (stay tuned for that!), suffice to say there are many linkages between Newport and Epstein’s work. Newport argues that the ability to concentrate intensely is a valuable professional skill. Concentration is a skill that must be trained. By carving out the ability and time to work deeply and without distractions, we not only become more productive and professionally valuable. We require our brains to get better at concentrating. Paradoxically, Deep Workers also tend to be generalists, bingers who throw themselves into specific tasks without regard for short-term success. Similarly, the rewiring of our neurological pathways that Deep Work engenders is a firm analog to the “sticky” learning Epstein refers to throughout Range.

The Head-start in Music

Although it may not seem like it from my summary, Epstein does spend significant time discussing music. In fact, Range is the most articulate critique of Deliberate Practice I’ve encountered thus far.

To Epstein, music is usually the narrative lynchpin for the cult of the head start: focused work on a repetitive task, minimal deviation, and a kind learning environment. If one starts early enough, the requisite hours of practice can be achieved early enough to have a terrific head start. Classical musicians work primarily on algorithm: articulating a pattern that has worked in the past, applying previously successful techniques to a problem, and repeating. This thinking is effective because in classical music, many of the problems are old; repertoire that is pre-existing or is similar in affect or structure to a previous work. At the same time, classical training has been honed over hundreds of years to create musicians capable of tackling these familiar problems quickly and effectively. In this world, the primary measure of success is a head start: if the path is clear, leaving earlier makes sense! Thus, Deliberate Practice: a scientific method-inspired reflection technique designed to serve as the apotheosis of this sharpened path.

«But…»

Epstein’s case studies show that head starts tend to evaporate over time, as the match quality of the tortoises overwhelms the narrow skill of the hares. While these studies ignore the professional durability of a head start in music (more concerts create more concerts, and it’s challenging to break into a musical community when one is older) I do concur that time spend developing problem-solving, critical thinking is more important than algorithms in creating a durable professional career.Epstein argues that learning is more durable and applicable when it occurs through osmosis rather than error correction, although error correction seems to be how we teach classical music.

Epstein corrals a number of studies which seem to suggest that playing many instruments is more effective in developing musical expertise, that early dalliance seems more effective than early focusing. It seems that picking early and staying focused can create deep but narrow knowledge. But, isn’t creativity an area where expertise is about the ability to learn new things?

Deliberate Practice and “kind” learning environments

It follows from Epstein’s research that our old friend Deliberate Practice most definitely occurs within “kind“ learning environments.

Reconciling Deliberate Practice, generalization, and Design Thinking

I do believe that deliberate practice and generalization can work hand in hand, but it requires laying off the focused work until the sampling period is complete, and acknowledging that not all musical professions are clear-cut and kind enough to include deliberate practice at all junctures.

Deliberate Practice is essential when the goal is clear, the parameters set. Here, our biases are essential to refinement, and domain specific knowledge is a shortcut to effective practice. Much of my work, though, involves working collaboratively with composers on first interpretations of new work. In these more wicked musical learning environments, the lack of a clear-cut precedent frequently short-circuits my training, negating the benefits of Deliberate Practice. In these situations, where the goal is not clear and experimentation is required before the material is set, Deliberate Practice seems less prescient than design thinking solutions: ideation, short-term PREtotypes, failing fast, and outside-in solutions. Knowing when to use each type of work is an essential skill, it seems!

Cal Newport: Deep Work: Rules for Focused Success in a Distracted World.

Cal Newport’s Deep Work was a transformational tome for me. In fact, I was such an ineffective worker that it took years after the initial recommendation from Matt Barnson to actually read the book. Deep Work is both a philosophical and pedagogical tract. It teaches us why focusing deeply is important to our careers, and shows us how to move towards meaningful changes in our work habits.

I’ll save the takeaways for another post. Suffice to say that generalists are Deep Workers, Deliberate Practice is Deep Work, and if we all had a few more nudges we could eliminate much of the mental pond scum that sullies our thoughts.

Larger Takeaways

Suffice to say, there is a lot to unpack here. In these works, there exists a common thread of connecting science to psychology, of answering why humans behave the way they do and to what extent our evolution and biology predisposes us towards certain outcomes. These books also touch the biological conflict between our individualism and our groupish overlays. As humans, we act in our self interest, except when we don’t. Beginning to understanding how and when our group instinct is activated has been transformative in my thinking. Finally, each of these books combines biology, psychology, and physiology to discuss the tools we need to function in our contemporary society, a “wicked” learning environment if there ever was one. Interdisciplinary and intermodal problem-solving, avoiding behavioral biases, setting isolated time to focus, and understanding how morality binds and blinds us can go a long way to activating the best version of ourselves.

I’ve found incredible utility from these books in my percussion playing, teaching, and curating. I’d love to hear from you (if you made it this far) about your takeaways, and recommendations for more books for me to butcher in summary.

Turning

A(n HD) video from the premiere of Paul Kerekes’ “Turning,” live at the Norfolk Chamber Music Festival. Hannah, Paul and I are excited to take the rest of the piece for a spin February 7th, on Yale’s New Music New Haven series! More information is forthcoming… Not shown: almost two minutes of page re-arranging pre-downbeat.

Squeak Squeak, Plunk Plunk.

I'm back from six amazing weeks at Norfolk (more on that soon) and all moved out to gorge-s Ithaca (more on THAT soon, as well), but I wanted to share this live recording Hannah and I made of Martin Bresnick's Songs of the Mouse People, a fabulously clever (albeit brief) meditation on Kafka's last short story. It's one of many shiny new live recordings on the new New Morse Code website. Like all labors of love, it's a work in progress, so keep checking back as Hannah and I update and tweak things, edit video, and argue about font sizes and margins. If you're more interested in solo music, check out my new video of the vibraphone portion of Manoury's Livre des Claviers. Enjoy, and stay tuned for more news, a new calendar page, important links, recordings, musings, reports, and complaints!